Lincoln through John’s eyes

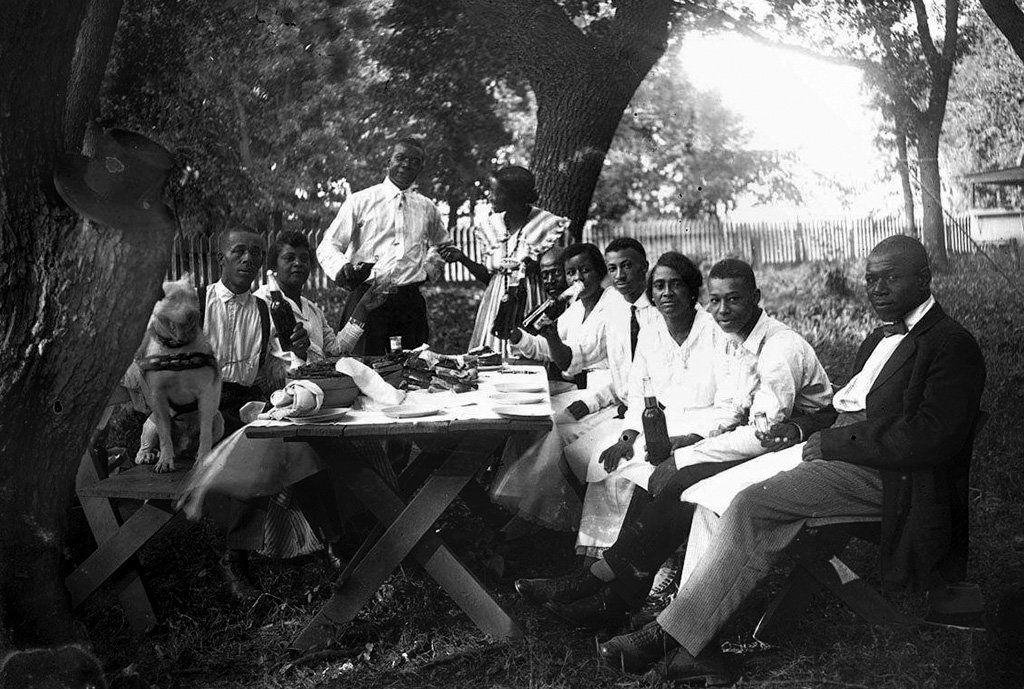

Backyard picnic, Lincoln, Nebraska, ca. 1910-1925

Public domain photo by John Johnson, Developed by Douglas Keister

How a Nebraska native preserved African American stories in the early 1900s

Beams of sunlight cast shadows across the scruffy lawn, encompassed by a neat picket fence. A slightly warped wooden picnic table rests beneath the branches of a large old shade tree. On the planks of its top lies starched ivory napkins, spotless porcelain plates and enough food to feed the ten guests surrounding the table. They’re comfortable with each other. Squeezed onto the matching wooden benches that line both sides of the feast. A couple, the hosts, stand at the head of the table. She leans towards her husband. A grin splits her face as he offers a meek smile to the camera. The guests wear their Sunday best. The women are in light sundresses and the men sport bright collared shirts. There is an air of contentment as guests grip their glass bottle-bound drinks and gaze leisurely at the camera. This scene, “American Picnic” (circa 1910-1925), was captured by amateur photographer and Lincoln resident John Johnson.

Johnson’s photographs of African Americans and immigrants during the early 1900s remain immensely significant to their representation in the historical record. He was born in 1879 to Civil War veteran and escaped slave Harrison Johnson and his wife, Margaret. Johnson graduated from high school, then attended college at the University of Nebraska. He found work as a janitor for the Lincoln Post Office and Courthouse, manual labor still being one of few types of employment available to African Americans. When he wasn’t cleaning buildings, Johnson was behind his bulky camera. His roughly 500 photographs stand apart from many professional shots from that time for two reasons. The first is his preferred setting. Unlike professional photographers who used studios and backdrops, Johnson met his subjects where they lived out their daily lives, in places they were familiar with. They can be seen on their front porches, in their homes or on the street. Their poses and expressions are relaxed and comfortable. The second distinction lies with the subjects themselves. Johnson focused his efforts primarily on minority groups. His photographs tell the story of hundreds of Nebraskan African Americans, providing visual documentation on the lives of a group so underrepresented in the historical record.

John Johnson’s story and work is not an isolated case of African American contribution to a society that significantly limited their opportunities. The historic value of his work was not fully realized until 1965, when a 17-year-old aspiring photographer, Doug Keister, bought a seemingly random box of 250 of glass negatives to practice making prints with. Now, 60 of Johnson’s prints are displayed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C.

Stories like the ones shared by Johnson’s photographs enrich our perspective and highlight experiences that may have been otherwise overlooked. These stories of everyday people living everyday lives are just as important as the famous characters that dominate narratives of African American history. Hearing and sharing these stories are what Black History Month is all about.

By: Sidney Needles