Dada: Nothing, Nothing, and More Nothing

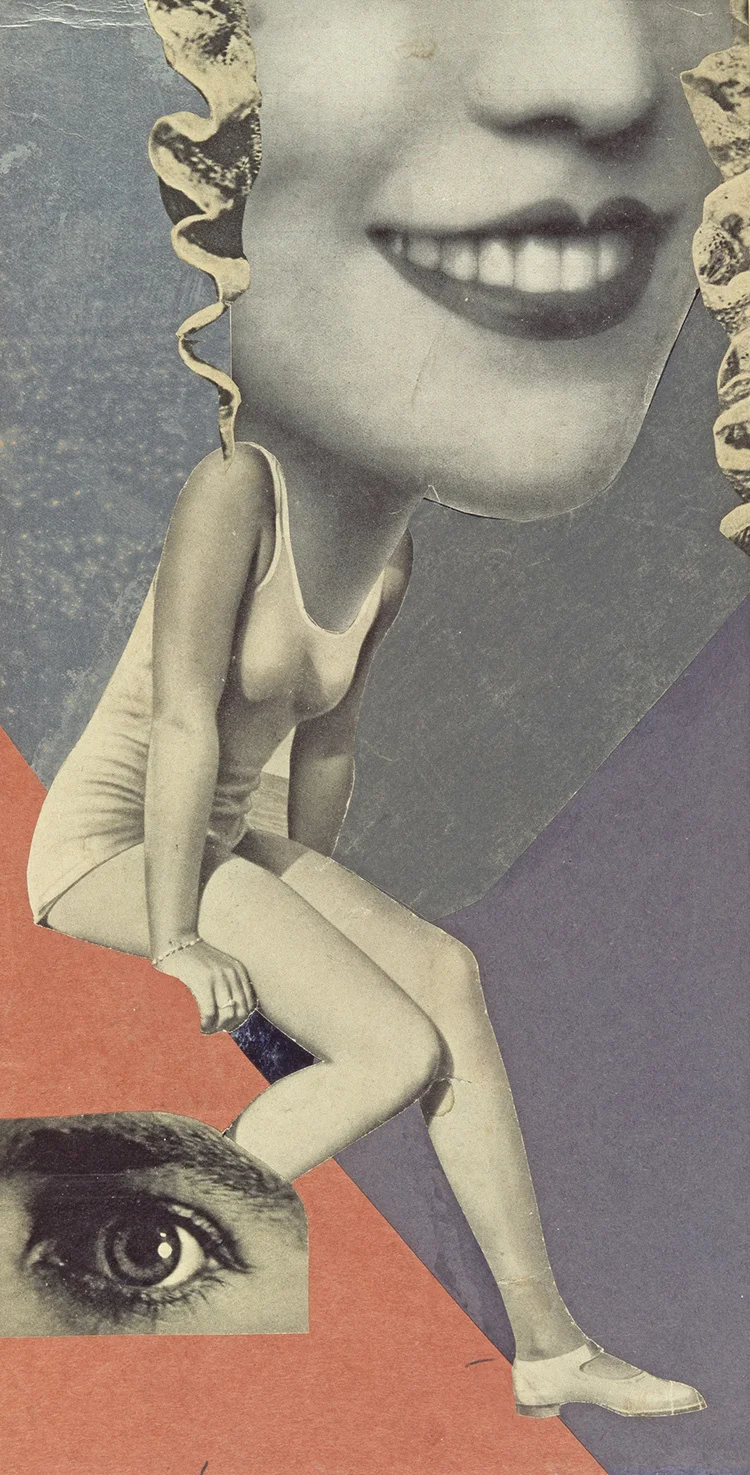

Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party) by Hannah Höch | PC: theartstack.com

Memento Artem

Bombs bursting, shouts of troops in the trenches, gunfire everywhere. The Great War or World War I left a scar on the face of the world. From the flames of warfare, a new movement emerged in the the art world.

Dada surfaced in response to the atrocities of World War I, the bourgeois class and the questioning of the corrupted parts of society that may have caused the war. Dada’s roots can be traced back to Zurich, Switzerland but spread to other major cultural centers like New York City and Paris.

The creator of Dada was the writer Hugo Ball who, in 1916, created a satirical night-club in Zurich called the Cabaret Voltaire, and a magazine entitled Dada. Around him a group of artists and poets formed. This ragtag group of artists created a philosophy and strategies to describe how to create new forms of both literary and visual art.

Dada sounds like a weird name though right? Well, the story goes that the group in Zurich used chance to pick the name of their movement. The most widely accepted story is that a paper knife was shoved into a French-German dictionary. The knife pointed to the French word dada or “hobby-horse”. However, the word holds meaning in multiple other languages as well which conveniently aligned to a core value of the group to open up their movement internationally.

Dada launched an unrelenting attack on traditional ideas and concepts associated with art, aiming to create new ones. Dadaists usually can be divided into two schools of thought: those who were creating from genuine outrage, and those making the weird and wild. In this rejection of traditionalism, many Dadaists used found objects, photomontage and collage to challenge the old-school mediums of painting and sculpture.

Dada also rejected the idea of the establishment. Although, it contradicted itself with this thought. Dadaists would often say, “Dada is anti-Dada.” However, most mocked the art establishment through their creations.

Trust me, Dada gets weird. Cadeau, or “Gift” in French, by Man Ray is an iron with a row of nails projecting from its surface. This object perfectly exemplifies what Dada aimed to do. A normal object became something weird, sadistic and unnatural in a way that escapes the realm of logic and understanding.

Another example is Hannah Höch’s Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party). This collage is a response to societal standards of gender in her works the artist’s world. Through the use of magazine pictures, which glorified beauty standards, she makes the viewer take a good-hard look at how we define beauty, femininity and domesticity.

So how can Dada apply to us today? It’s the underlying thought of questioning the status quo and embracing the absurd that might benefit us. In a time of division and tension, we can look at society through a modern Dadaist lense and think hard about what doesn’t seem right. We also can work through such things by utilizing our imaginations to find the weird and unusual in the world that can evoke a sense of wonder and intrigue. Although, maybe as the Dada quote by Francis Picabia goes, we may find “... nothing, nothing, nothing.”

Cameron Cizek is a junior studying computing.