Jo Baer: Keeping it Minimal

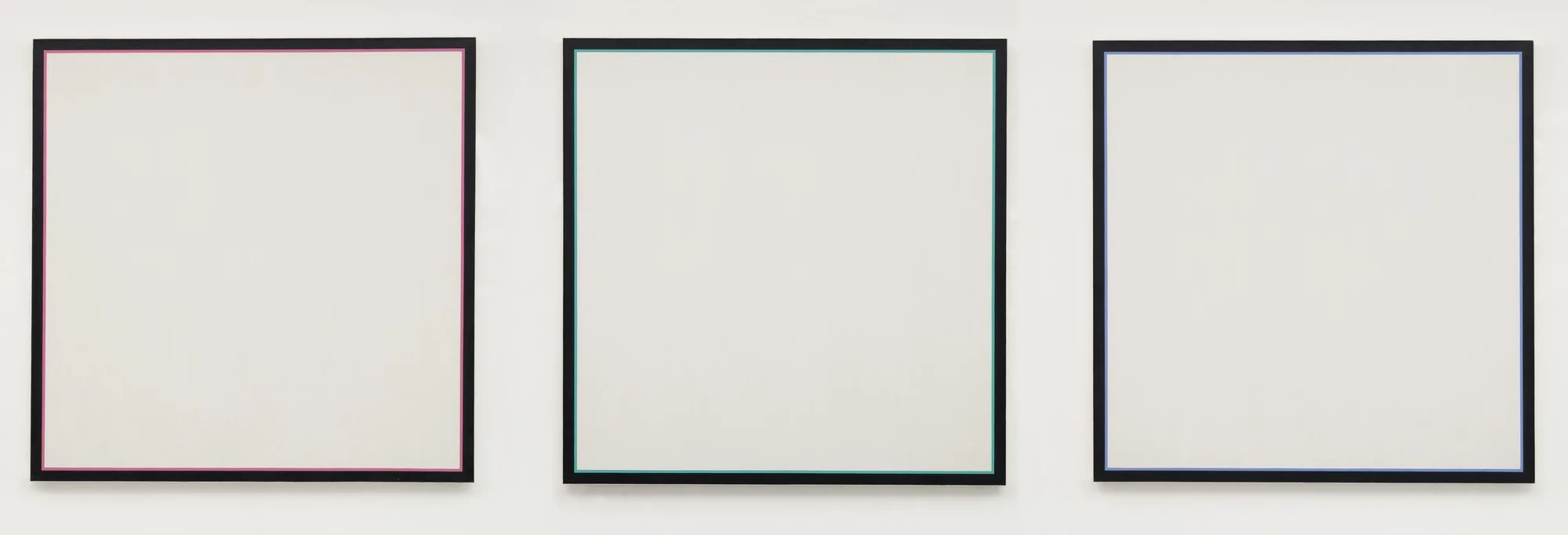

Primary Light Group: Red, Green, Blue | PC: moma.org

Memento Artem

Three canvases line a wall at the MoMA. At first they appear to be blank, white canvases lining a wall with a black outline around them. The thought, Why are these here? comes to mind.

However, upon closer inspection, the canvases aren’t empty. Rather, each canvas has a band of color running around the canvas followed by a thick black band. Most people reaffirm their questioning of why such pieces are in a museum and move along. Others may take the time to look at these pieces and remain open to them.

These are the lucky minority. As you take the time to appreciate the work, something spectacular happens. The colors shift and interact with each other in amazing ways that seem to change the overall tone of the space. This is what Jo Baer wanted viewers to experience when she painted Primary Light Group: Red, Green, Blue.

Jo Baer is among the most celebrated contemporary artists. Her work can be found across the globe, from the US National Gallery of Art to the National Gallery of Australia. Her roots can be traced back to the minimalism movement of the 1960s and early 1970s where her works were strongly influenced by her education in perceptual psychology.

What’s minimalism? “Minimalism was a reaction against the heavily expressive and metaphoric painting of the abstract expressionists”, says Union College Assistant Professor of Art and Graphic Design Alan Orrison.

“The goal of the minimalists was to drastically simplify their materials and compositions, thereby eliminating symbolism, emotion, and metaphor. They were interested in the art object in its most literal sense, as a physical entity existing in a specific space.” Baer’s work does exactly that and more.

However, Baer, as a painter, wasn’t favored among all her contemporaries. Minimalist sculptors such as Donald Judd and Dan Flavin made the controversial claim that painting was a dead medium. “In saying that ‘painting is dead’, sculptors like Judd and Flavin would have argued that painting can never be completely free from metaphor”, says Orrison.

“Judd and especially Flavin's work was all about the experience of the viewer. Judd was interested in how the visitor to the gallery navigated the space, scale and perspective of this pieces.” Orrison continues, “Flavin's fluorescent light installations are about transforming and sculpting the gallery space itself.”

Baer tried to communicate with these artists through private letters about their disputable claims. However, she received no answer from them. So, she decided to say her peace publicly in a letter to the publication Artforum in 1967. “I got sick of being told that I wasn’t radical when I knew very well that the ideas behind Minimalism had been worked out by [Frank] Stella and by [other painters]. And these “object-makers” were Johnny-come-latelies”, said Baer.

Baer wasn’t a big fan of her contemporaries either. “Just because you can bump into sculpture doesn’t make it that much better; actually, I think it makes it that much worse. An object takes up space, and the idea is no longer clear.” Besides this dispute of mediums, all minimalist artists seemed to have an overlapping goal. Orrison says that these artists were “interested in the viewer's physical interaction with [their] work.”

So to those who have the question Why are these here? The answer is: they’re here for you. Minimalism was a movement meant to empower the viewer with a space to interact with art. It's a movement allowing you, even for just a moment, to be fully present and experience art in its fullest.

Cameron Cizek is a junior studying computing.